The debut crime novelist offers some alternatives to the fanciful solutions and foggy London of Sherlock Holmes

Tomado de guardian.co.uk

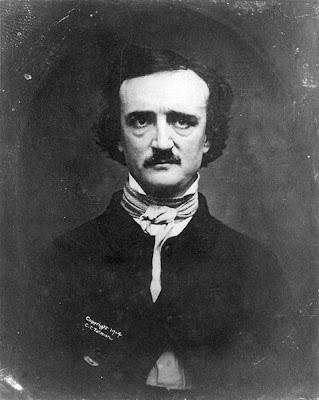

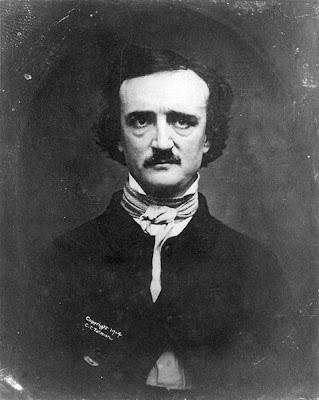

James McCreet is the author of The Incendiary's Trail, a Victorian detective thriller influenced by the early works of Edgar Allan Poe and drawing on detailed historical research. Our review described it as "splendid… full of vividly depicted squalor and grotesquery".

The Incendiary's Trailby James McCreet

Buy it from the Guardian bookshopSearch the Guardian bookshop

McCreet was born in Sheffield in 1971. He is currently at work on the third book in the series alongside his job as a copywriter.

Buy The Incendiary's Trail at the Guardian bookshop

"Sherlock Holmes and his predecessor, Edgar Allan Poe's Auguste Dupin, were always fantasy detectives. Their powers of deduction often bordered on the paranormal, and what passed for deduction was more usually just imagination. In fact, the real Victorian detectives, though more prosaic, were much more interesting. Armed with little more than their wits and a sharp eye, they were required simply to outsmart the criminals. No DNA, no databases and until the very end of the century no fingerprints – the true detectives of that period were perhaps the purest of the form, either literary or factual. Their London was one that straddled industrial modernity and Elizabethan poverty: a breeding ground for crime, and for stories."

1. On Murder by Thomas de QuinceyThe old opium eater's series of articles about the real-life Ratcliff Highway murders pre-dated Poe and arguably have a claim to be the true origin of detective fiction. The Postscript in particular is a thrilling literary reconstruction of how the murders were committed, tracing how "the silent hieroglyphics of the case betray to us the whole process and movements of the bloody drama".

2. The Mystery of Marie Roget by Edgar Allan PoeThis overlooked short story was the follow-up to the seminal Murders in the Rue Morgue and was based on a genuine murder. Eschewing some of the more ludicrous mental gymnastics of Rue Morgue, this one instead has the detective solving the case merely by reading newspaper accounts of it. Fanciful it may be, but the logic is powerful, the parallels with literary criticism are clear, and the true victim lurks tragically behind it all.

3. Bleak House by Charles DickensDickens was fascinated with the idea of detection and spent much time with real detectives to produce journalism including "The Modern Science of Thief-Taking" and "A Detective Police Party". In Bleak House, he is one of the first authors to feature such an investigator in the form of the sober and practical Inspector Bucket, very likely influenced by the real Inspector Field.

4. The Suspicions of Mr Whicher by Kate SummerscaleThis deservedly popular book examines a genuine case to get under the skin of real investigative techniques and provide a useful background to the origins of police detection. The "hero" Mr Whicher was indeed an archetype of the Victorian 'tec who applied a certain objective "x-ray" vision to the people and society around him.

5. The Moonstone by Wilkie CollinsA competitor with Rue Morgue for the sheer preposterousness of its solution, this was another Victorian celebration of the genuine detective. The character of Detective Sergeant Cuff was allegedly based on the real-life Mr Whicher and exhibited the true traits of the historical detective: method, rationality, pragmatism and a healthy sense of distrust about what one might be told.

6. Memoirs of a Bow Street Runner by Henry GoddardThis relative rarity is hailed as one of the few authentic accounts of a real detective and as such provides fascinating insight into how these men went about their investigations without the aid of science or technology. Goddard was a detective with the Runners until they were superseded by the Metropolitan Police in 1839, but he worked privately (and lucratively) for years afterwards.

7. London Labour and the London Poor by Henry MayhewMoriarty, like all master criminals, was pure imagination. Journalist and social historian Mayhew went out in the 1850s to interview the true downtrodden denizens of the underworld: the conmen, prostitutes and chancers who stayed alive on their wits alone. My favourite – the man who sold old newspapers in sealed brown-paper wrappers under the pretence they were obscene prints.

8. Fingerprints by Douglas G BrowneNovelist Browne also produced some important history of the art, including a notable book on Scotland Yard and the Metropolitan Police's Detective Force. His volume Fingerprints documents the development of forensic science from its earliest origins and lends a fascinating parallel to the pseudo-scientific larking of Sherlock Holmes.

9. A Dictionary of Victorian London by Lee JacksonFor all the investigative audacity in Conan Doyle's work, London itself remains little more than a backdrop to the narrative. Dickens knew that the city was the real star, and Lee Jackson's delicious collection of contemporary sources paints a picture of a city that often seemed too weird to be real, but always too real to be entirely fictional.

10. Victorian London by Liza PicardAmong a multiplicity of books on the period, Liza Picard's social history has a humour and personality that really brings London to life. Her chapter on the smells of the city does more than any cinematic cliché of fog to evoke just what it must have been like to live and work there. These were the very streets upon which Victorian crime played out.